For thousands of years, most details of ancient Egypt’s culture, history, customs, and beliefs, including the names of places, things, and individuals, were unknown. The knowledge was bound up in frustratingly indecipherable lines of pictographs (words or phrases in pictures) called hieroglyphs.

This is the story of how we figured them out.

Drowning in Hieroglyphs

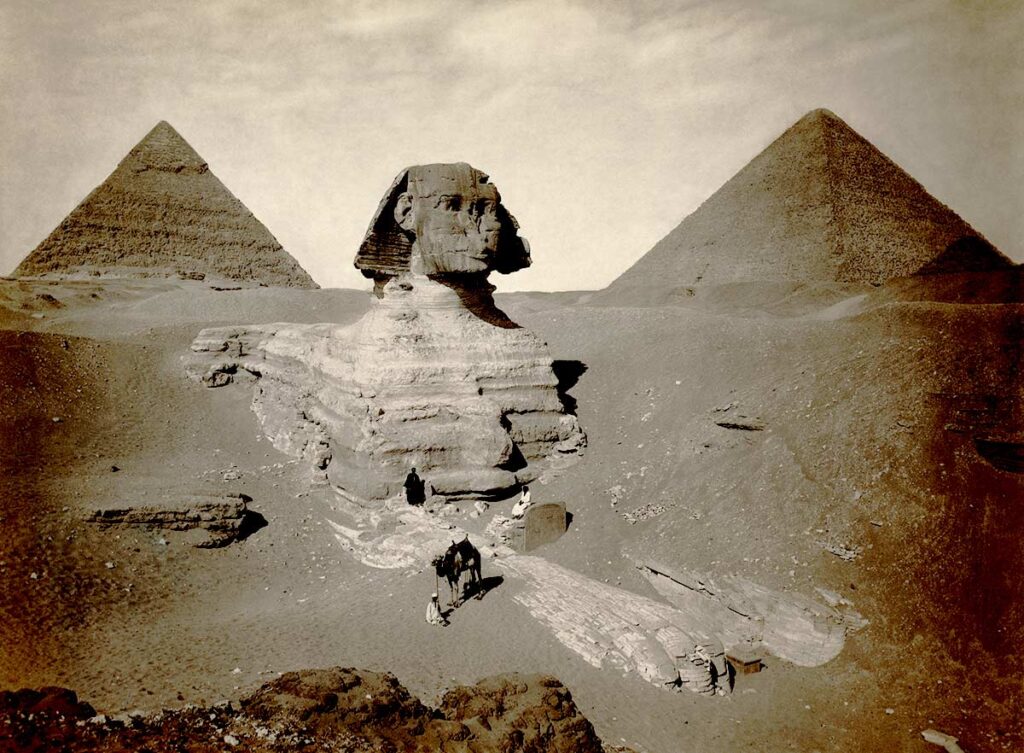

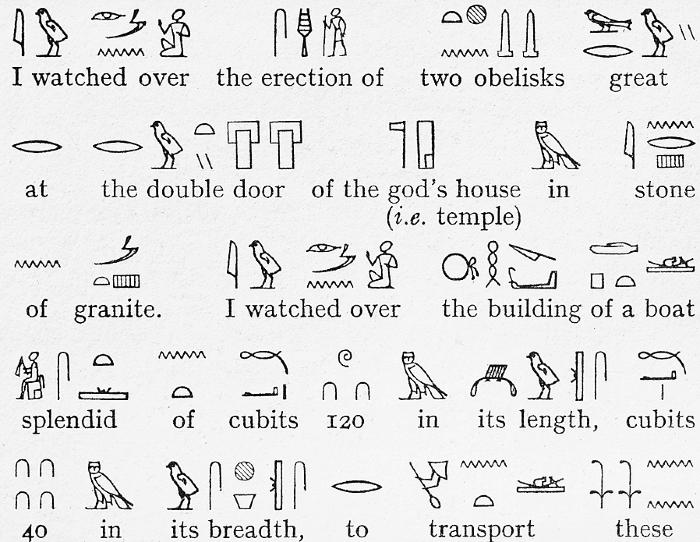

If you’re an archaeologist digging around in the physical remains of ancient Egypt, hieroglyphs are everywhere. They were painted on and sculpted into statues and walls, inscribed into stone artifacts, columns, and obelisks, painted onto papyrus scrolls, and woven into and painted onto linen.

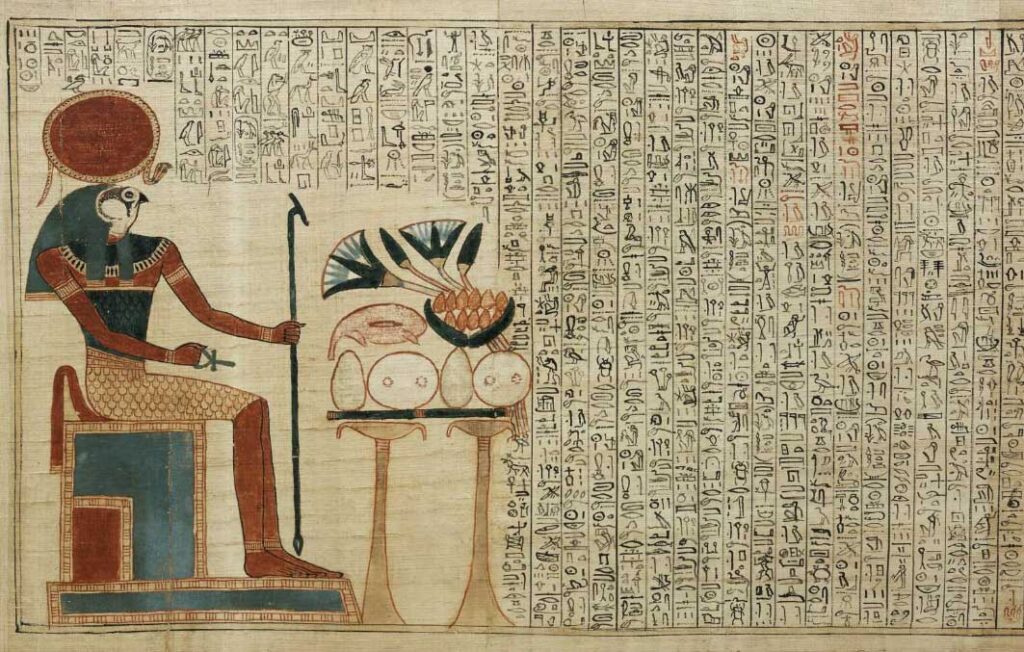

“The Papyrus of Ani, The Book of the Dead,” or more properly, “The Book of Coming Forth by Day,” “The Book of Emerging Forth Into the Light,” or “The Book of the Great Awakening” was stolen for the British Museum from an Egyptian government storeroom in 1888 by Sir E. A. Wallis Budge, perhaps the greatest Egyptologist ever (and maybe the sneakiest one). Before shipping the manuscript to England, Budge cut the 24-meter (78-foot) scroll into thirty-seven sheets of nearly equal size, damaging the scroll’s integrity at a time when technology did not exist to put the pieces back together. The scroll is a guide to rituals for the dead, spells and incantations, and instructions for disembodied spirits on how to behave in the Land of the Gods and the Dark Underworld.

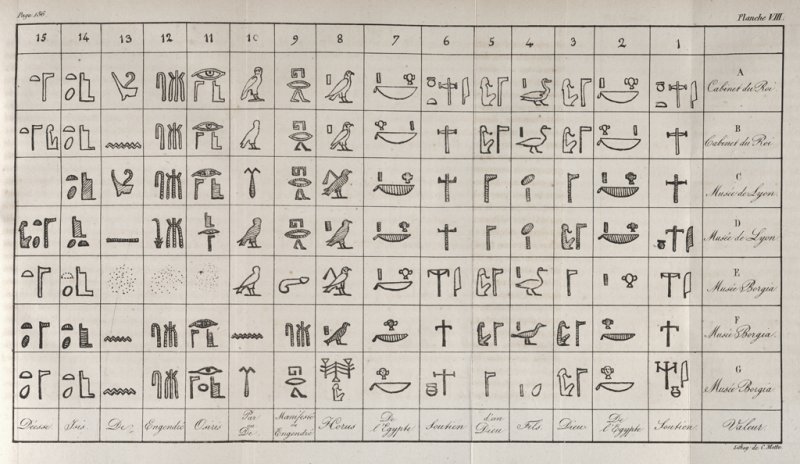

By the early 19th century, there were thousands of examples of hieroglyphics to draw upon, with more constantly being uncovered as French, British, and Swiss archaeologists excavated newly found tombs. Egyptologists of Europe had acquired many reproductions of the hieroglyphs to study, rubbings of inscriptions, and drawings. Still, without some kind of legend to the pictographs—the pictures that each meant a word or phrase—the complexity of the language seemed impenetrable. The inescapable fact was that the last person who could read and understand hieroglyphics had likely died nearly 2,000 years earlier.

Specifically, it ended in the 5th century when the Romans shut down the last of the Egyptian pagan temples. Despite efforts to understand hieroglyphs through the Middle Ages, they remained a black box.

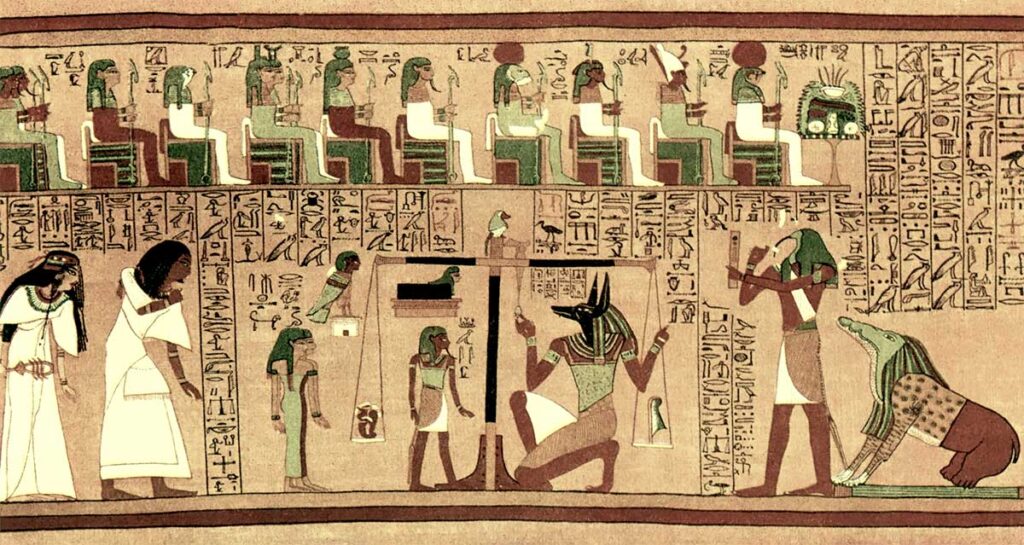

Let’s take a closer look at the image above.

The Great Ennead, a group of nine major gods and goddesses, shown seated at the top, waits. The person’s soul, the Ba, shown as a small, human-headed bird to the left of the scales, looks on nervously.

Anubis, the god of funerary rites, with the black head of a jackal, performs the Judgement by carefully weighing the soul’s heart (its essence) against the Feather of Ma’at (the Order of the Universe). If it weighs less than the Feather, it indicates the person lived a good life and would be rewarded everlasting joy in the Field of Reeds, the Afterlife. But suppose Anubis finds the person’s heart heavy from a life of hatred, dishonesty, and indecency. In that case, the demoness monster Ammit, terrifying, with the hindquarters of a hippo, the forequarters of a lion, and the head of a crocodile, is ready to devour the soul forever.

Thoth (with the head of a Sacred Ibis), god of the Moon, wisdom, knowledge, writing, hieroglyphs, science, magic, art, and judgment, stands in front of Ammit, ready to permanently record the result.

Not that we would know any of this without being able to read the hieroglyphs, which we couldn’t until the mid-1800s. Good thing we have a powerful cheat code called “living in the 21st century.”

It’s All Greek to Me

Hieroglyphics was de facto a dead writing system and—although it appeared everywhere around Egypt’s mummies, in the remnants of writings on papyrus parchment scrolls, and in what survived of their monuments, tombs, and temples—the hope of deciphering it seemed frustratingly lost to time.

In 4,000 years, no archaeologist had ever discovered an ancient Egyptian language textbook or a hieroglyphics primer for Egyptian schoolchildren. Getting a handle on this strange language looked to be impossible.

“The inescapable fact was that the last person who could read and understand hieroglyphics had likely died nearly 2,000 years earlier.”

But that would change, and it would start when Emperor of France Napoleon Bonaparte decided to invade Egypt in 1798 to try to ruin some trade routes for Britain, with whom he was at war.

A Strange and Lucky Discovery

The summer of 1799 was the middle of Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt, and troops led by French officer Pierre-François Bouchard were scouting for building materials they could use to fortify their encampment at Fort Julien near the town of Rosetta ahead of a key battle. They were collecting stone from the ruins of the 15th century Ottoman Fort Qaitbay when they discovered a unique object inside the outer wall, something the Ottomans had used as just another piece of stone in the wall.

The Stone

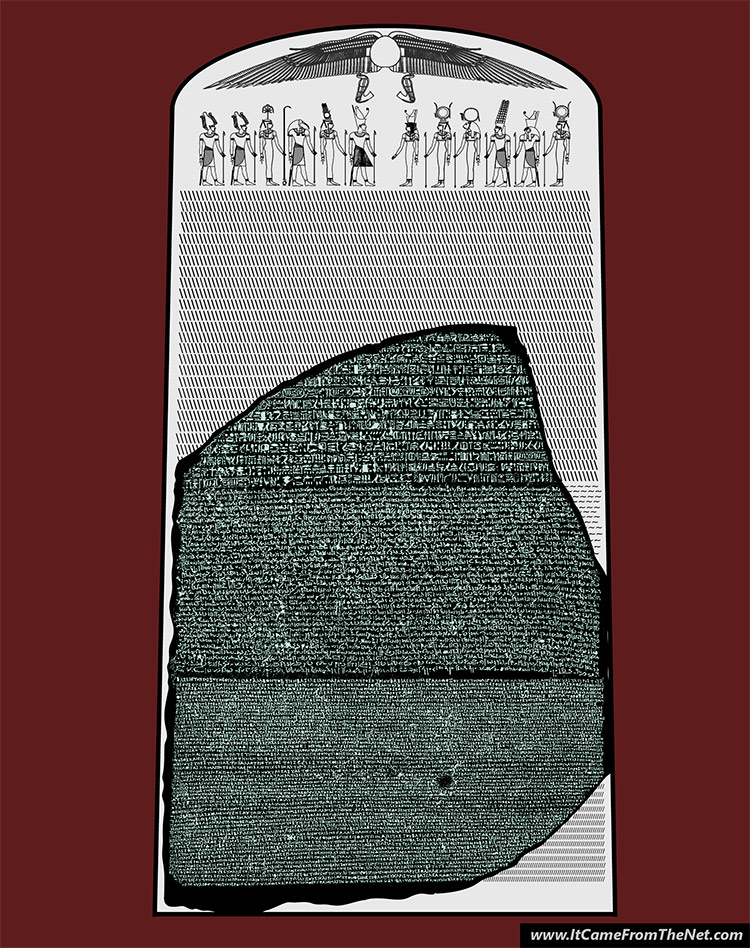

It was a black, flat, thick stone tablet composed of granodiorite, broken in several places, its face covered in lines of engraved writing in three different languages: at the top, 14 lines of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs; the middle, 32 lines of ancient Egyptian Demotic—the transitional cursive script that bridged hieroglyphics to current Egyptian Coptic—and, at the bottom, remarkably, 54 lines of Ancient Greek.

“In 4,000 years, no archaeologist had ever discovered an ancient Egyptian language textbook or a hieroglyphics primer for Egyptian schoolchildren.”

The stone was engraved with the same information but written in three different languages!

Created in the Greek Hellenistic period of Egypt, it was the broken fragment of a stele—a stone monument erected in public or in a temple to serve notice of some important dictate. This piece of stone describes a decree issued in Memphis, Egypt, in 196 BC by four priests of King Ptolemy V, intended to re-establish and assert the rule of the Ptolemaic kings over Egypt. It said that the Memphis temple priests supported the Ptolemaic king. (All of the Ptolemaic queens, by the way, were named Cleopatra, I through VII, where VII, the last pharaoh of Egypt, is the one everyone’s heard of.)

It’s All Greek to Me. OMG It Actually IS Greek!

The stone was created during a short, unique time in Egypt’s history when people in various communities spoke and wrote in three languages, all considered worthy of important public pronouncements. And because scholars knew precisely what the ancient Greek portion said, they hoped it would be possible to work backward and discover what some of the individual hieroglyphs meant. The object was, potentially, a kind of ancient Google Translate, a primer for ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs!

Officer Bouchard would accompany la Pierre de Rosette—what had already become known as the Rosetta Stone—to Cairo so scholars could study it. Napoleon himself took an interest and personally inspected the artifact.

Scholars made print reproductions of the stone’s inscriptions by rolling ink directly onto its face and pressing paper into the ink, using the whole thing as a giant printing block. The scholars sent the reproductions back to Paris for analysis.

“It was a black, flat, thick stone tablet composed of granodiorite, broken in several places, its face covered in lines of engraved writing in three different languages.”

Scholars across Europe, historical linguists, and philologists (those who study ancient languages) would immediately set out to unlock the mysteries of the hieroglyphs, a quest that would eventually take 20 years.

The First Breakthrough: The Greek

When the English defeated the French in 1801, the Rosetta Stone was one of a set of objects that Napolean turned over as part of the terms of surrender of the Treaty of Alexandria. The British Navy moved the Rosetta Stone from Cairo to London and transferred it to the British Museum. Within two years, British classical scholar Richard Porson would publish his reconstruction of the likely text of the missing ancient Greek corner of the stone.

The Second Breakthrough: The Ovals

Further progress came in 1814 from British scientist Thomas Young, who determined that the cartouches—the hieroglyphs enclosed in ovals—contained the phonetic spellings of names, including King Ptolemy V, who was referenced in the stone’s ancient Greek section. This finding confirmed a long-held belief that the cartouches were the names of people, as archaeologists had seen them in tombs. Young also figured out the right direction in which to read the hieroglyphs.

The Big Breakthrough: The Transliteration

Years later, in 1822, French philologist Jean-François Champollion announced the completion of the hieroglyphs’ transliteration—the translation between languages. He determined that some signs were alphabetic, some syllabic, and some determinative, standing for the whole idea of the object previously expressed. He also realized that the hieroglyphics were a translation from the Greek and not, as had been believed, the reverse! Champollion had intensively studied the Egyptian Coptic language—along with many others—while researching Classical and Biblical accounts of Egyptian history, religion, and toponymy.

“The object was, potentially, a kind of ancient Google Translate, a primer for ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs!”

For the first time, archeologists had a reasonable idea of what the glyphs represented. However, it would be decades before they felt confident in their translations. Archaeologists would discover similar steles years later that would further help to complete their understanding.

Today, the total number of words in ancient hieroglyphic texts is over five million, and we understand almost all of it!

How Hieroglyphs Work

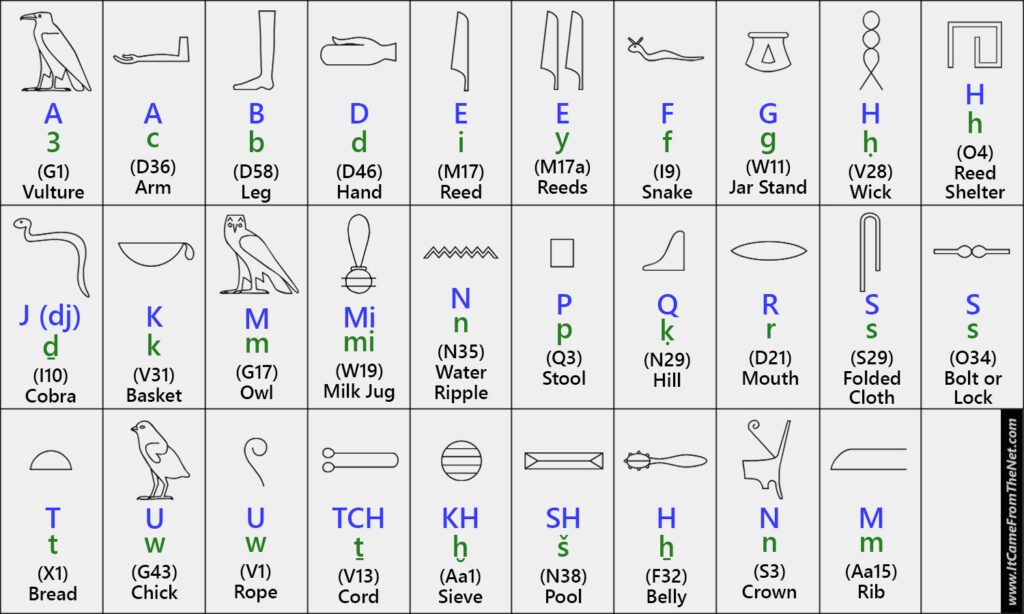

This is a brief overview of the discoveries of Egyptologist philologists like Jean-François Champollion and Sir Alan Gardiner, who developed comprehensive hieroglyphics dictionaries and the codes to reference individual glyphs (e.g., G1, N35, S29).

Pictures That Mean Sounds and Ideas

Each hieroglyph represents a phoneme (a speech sound) or an idea (an object, a concept). The phonetic glyphs could be a vowel or between one and three consonants.

The hieroglyphic phonetic alphabet, here mapped onto phonemes Westerners are more familiar with, represents verbal sounds (phonemes) in their language and forms the basis of their writing system. The chart above is incomplete but gives you an idea of how Egyptians used objects and creatures from their environment as hieroglyphs. It covers most of the basic phonemes, shown with their sounds, Gardiner codes, and meanings.

If you’re a good student, the chart might be enough to let you attempt to read hieroglyphs aloud with an outrageous foreign accent that would have made ancient Egyptians fall down laughing.

When describing something, the Egyptians would write out the glyphs that stood for the phonetic sounds of how to pronounce it and then follow those with a glyph called a determinative that represented what the thing was. Most hieroglyphs are determinatives.

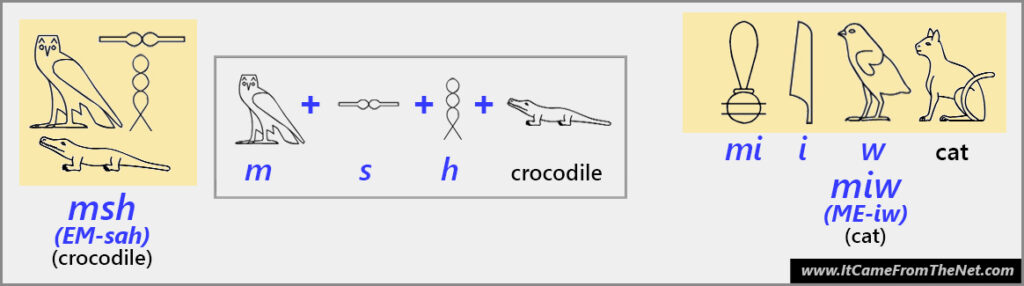

Here are examples of how to write the names of two animals. Each is composed of glyphs of how to say it and then a determinative of what it is. The glyphs for “crocodile” represent the sounds in the ancient Egyptian word for “crocodile,” “msh” (pronounced EM-sah), followed by the determinative hieroglyph of a crocodile. Similarly, the hieroglyphs for cat, or “miw” (pronounced ME-iw), combine the glyphs for mi, i, and w with a determinative of a cat.

And now you know that “cat” in ancient Egyptian is roughly pronounced “meow.”

Ways to Say “More Than One”

The determinative could be followed by short vertical lines called plural strokes, indicating that there were multiples of the thing. Or they would also use more than one of the same determinative to represent more than one of something. For example, “crocodile” with two crocodile glyphs meant “crocodiles.”

Writing the Names of People

If the hieroglyphs were inside a vertical or horizontal oval—a cartouche— they represent a person’s name. Cartouches were never used for gods’ names, but the last two names of the sitting king always appeared in them.

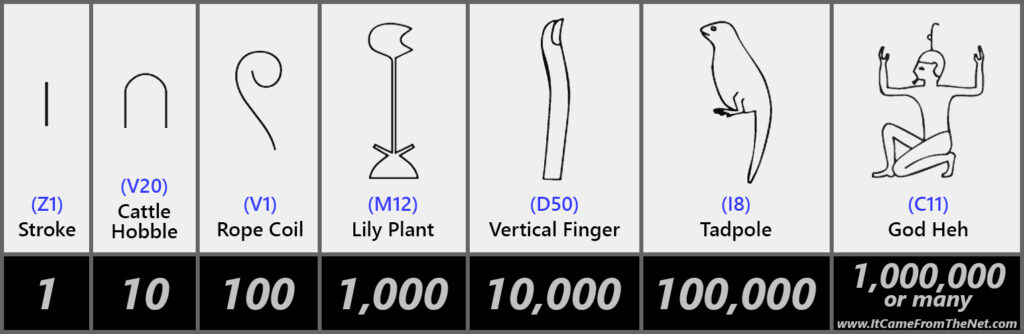

Writing Numbers

Ancient Egyptians wrote numbers by combining numeric glyphs so that they added up to the desired number. That small stroke was also used as the “plural stroke” mentioned above.

Using Fewer Hieroglyphs to Say the Same Thing

Bilaterals are shorthand glyphs that substitute pairs of common glyphs. They simply take up less space but are pronounced the same and mean the same as the two they replace. There are also trilaterals, replacing three glyphs.

There Was Room for Some Creativity

The layout of hieroglyphics was not, er, written in stone. The writer, painter, or sculptor had some freedom to lay out the images in the way they felt was aesthetically pleasing or communicated the best. Also, the writer/artist could take some liberties with the art of the glyphs, their line weight, and their color, as long as it was clear which ones they were.

Why Write with Pictures?

You might think writing with all these pictures seems inefficient, and you’d be right. Hieroglyphs were time-consuming to write (or engrave), they were all different shapes and sizes, and they took up a lot of space wherever you wrote them. This inconsistency and inefficiency wasn’t intentional. Languages aren’t normally planned out but instead arise organically out of a need to communicate. When they appear, they usually start evolving and don’t stop unless the culture using them dies out, slowly changing to become more efficient: more compact, more precise, less confusing (hopefully), and easier to say and write.

Hieroglyphics wasn’t the only ancient writing system to take the path of “each symbol means something different.” Japan and Korea write in pictograms, and there are tens of thousands of characters in written Chinese, although college-educated Chinese speakers tend to know only about 4,000. Similarly, there are roughly 7,000 unique hieroglyphs. However, the Egyptians typically used less than 1,000 of the most common ones.

There is a Better Way (Not Accounting for Taste or Tradition)

Inventing many different characters, each meaning something specific, is an obvious way to build a system of writing. It is much less obvious to realize you can, instead, use dramatically fewer characters but order them in thousands of different ways to get thousands of different meanings.

In other words, to instead use an “alphabet.”

Ancient Egyptians gradually realized this and transitioned away from hieroglyphics. The first huge evolution was the development of Egyptian Demotic, beginning around 650 BC. It was a flowing, cursive script version of hieroglyphics. Each large, common hieroglyph was replaced with a compact cursive character that could be written in lines read right to left, top to bottom.

Later, Demotic would further evolve to become modern Coptic Egyptian before being replaced by Arabic, both of those also being alphabetic languages in cursive script.

One Last Gift From the Stone

Once the mystery of hieroglyphs was cracked, the Rosetta Stone wasn’t quite finished giving up long-lost secrets. It was also instrumental in figuring out how hieroglyphs sounded when spoken thousands of years ago! Philologists were able to compare the phonetics of modern Coptic Egyptian to determine how the Demiotic Egyptian on the stone would have sounded, and they used that knowledge to correlate phonemes to the older version, the hieroglyphs.

If you could put a modern philologist of ancient Egyptian languages before a Pharaoh 3,000 years ago, they wouldn’t be mistaken for a native speaker. Still, they just might be able to understand what the Pharaoh was saying.

The British Museum, Permanent Keeper of the Stone

From 1802, the British Museum displayed the artifact publicly and kept it on display almost continuously. It is, in fact, the Museum’s most-visited exhibit. There have been calls, particularly in the early 20th century, for the British Museum to turn over the Rosetta Stone to one of the great museums of Egypt, for the stone to return home. Still, the chances of this ever happening are unlikely.

The British Museum was a co-signer of a 2002 joint statement from thirty of the world’s leading museums as a kind of final word on the matter. It read, “Objects acquired in earlier times must be viewed in the light of different sensitivities and values reflective of that earlier era…museums serve not just the citizens of one nation but the people of every nation.“

To be fair, though—and we’re nothing if not fair—many of the “stolen” relics and artifacts in the British Museum would have been lost forever if the museum hadn’t, let’s say, took them for safekeeping. Good examples are the extensive collections of Chinese art and artifacts possessed by the museum that would have been destroyed by Chairman Mao Zedong’s Red Army in 1966 when, during the Cultural Revolution, he ransacked museums and private homes, destroying any items he believed represented “bourgeois or feudal ideas.”

The Rosetta Stone Becomes a Concept

Today, the Rosetta Stone is so well-known that its name has become shorthand to describe a clue that is the crucial key required to unlock new knowledge.

The Birth of a New Archaeology

In the years following the revelations of the Rosetta Stone, an exciting new branch of archaeology, the scientific study of ancient Egypt, would soon attract thousands of professionals and enthusiastic amateurs across Europe and the United States of America.

It would be known as Egyptology.