The flesh of dead people hangs from the walls of museums and the homes of art collectors and families worldwide. It sounds like a morbid joke, but it’s absolutely true! This is the story of Mummy Brown.

Mummy Brown, A Color Like No Other

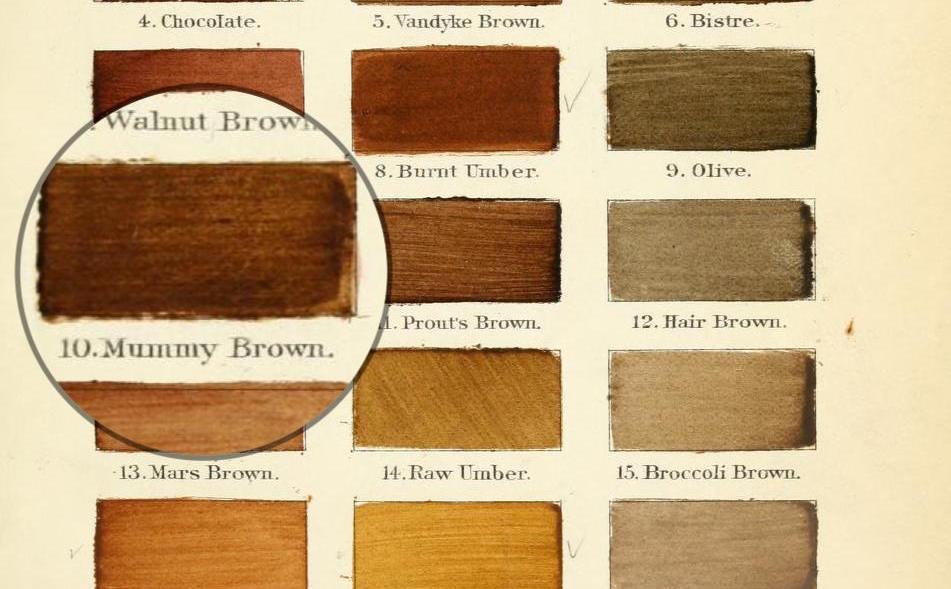

Mummy Brown, also known as Egyptian brown or Caput Mortuum (Latin for “dead head”), was a well-liked artists’ pigment in the 1700s and 1800s. It was used in countless thousands of paintings by many famous artists.

… Oh, and it was made from human corpses.

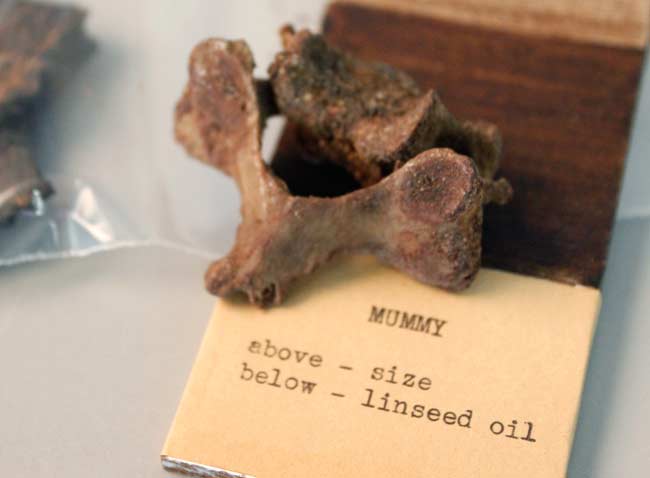

The secret of this popular pigment was a substance called Mumia, which was mummy powder, literally made by crushing and grinding to powder the desiccated, embalmed flesh of mummified people.

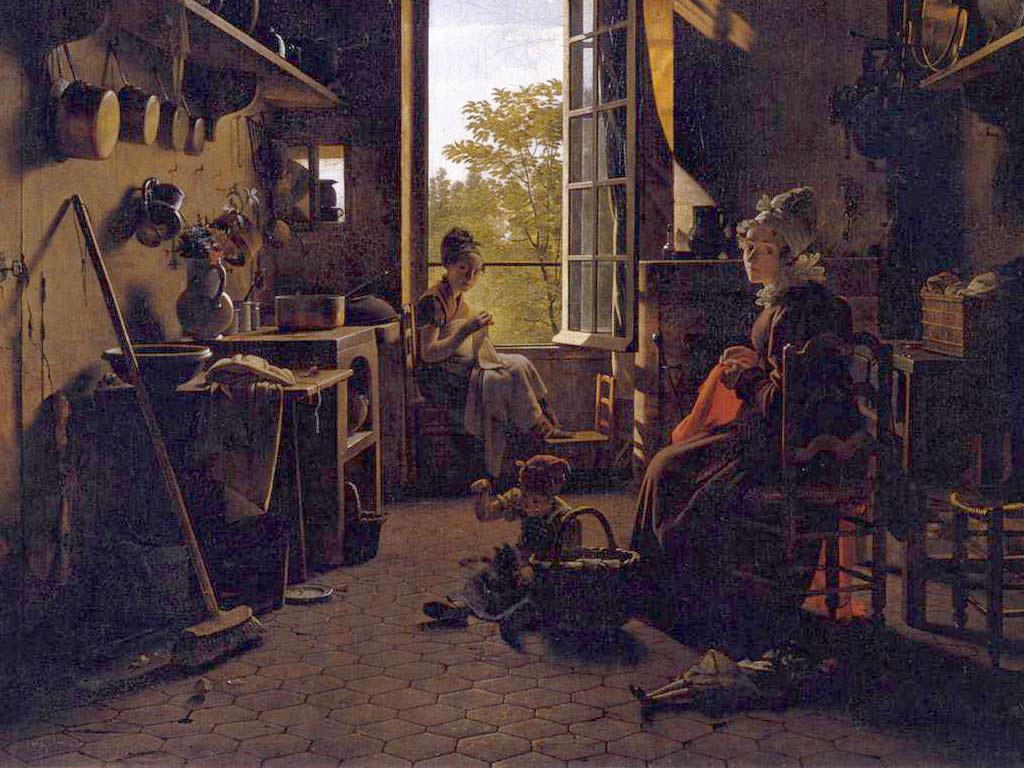

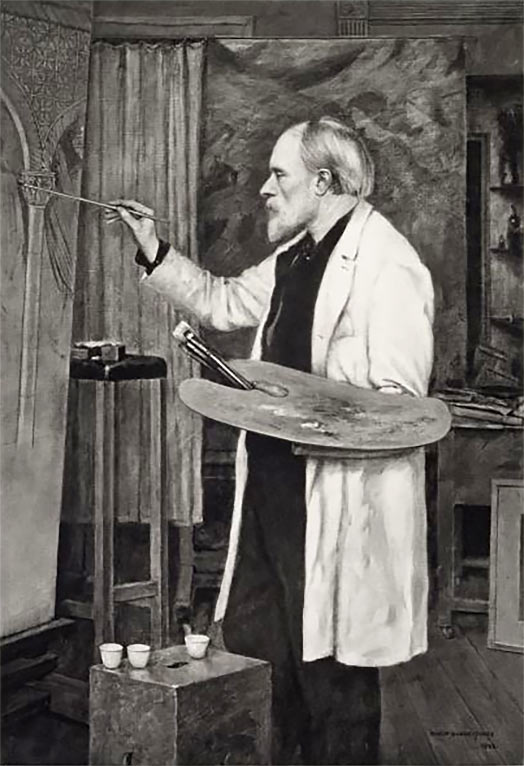

Your local art museum may have paintings made with Mummy Brown, as it was commonly used in oil paintings for over 300 years before the 20th century. For instance, this disturbing stuff was one of the favorite colors of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848, a seven-member group of English painters, poets, and art critics whose beautiful paintings were in demand. French Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix was another painter known to have used it.

The Gut-Churning Recipe for Mummy Brown

Combine the following:

- White pitch, a clear resin from pine trees

- Myrrh, a fragrant tree resin from the Commiphora myrrha tree

- Human mummified corpses, crushed, ground, and powdered

To create the Mumia powder, the pigment manufacturer would cut or break off manageable pieces of the mummified corpses for crushing, grinding, and powdering.

You have to wonder about the employees whose jobs it was to grind up human remains and how many dead people were hanging in the backs of shops and factories in the cities of Europe!

Putting the Parts Together

To create Mummy Brown—this thinnable, brushable pigment—manufacturers combined the Mumia powder with two substances obtained from trees: white pitch and myrrh.

Let’s Talk About Resin (Tree Gunk)

Trees create resins when they’re wounded. The tree attempts to cover the wound like a scab to prevent bacterial infection that could kill it. The resin creates a thick, air-tight seal and has anti-bacterial properties. Trees secrete it from special resin cells in the inner and outer bark.

While pine trees produce white pitch resin, myrrh resin is from the Commiphora myrrha, a small, spiny tree found in Ethiopia, Oman, Kenya, Somalia, and Saudi Arabia. When you damage its bark, myrrh hardens slowly into globules and irregular lumps called tears.

People have been using resins for many purposes for thousands of years. In antiquity, they were rare, expensive, and treasured. You may have heard that frankincense and myrrh were suitable gifts for a king.

A few of resin’s practical applications include:

- Use as an antiseptic, antimicrobial, anti-fungal, and antibacterial

- Use for dressing and sealing wounds

- Use as adhesives and glues

- Waterproofing for ropes, boats, roofs, and containers

- Use as a fire starter

- Use as a food ingredient, flavoring, or therapeutic to be eaten or drank

- Burning as an incense

- Fermenting to brew ale and wine

- Use in paints and pigments

Getting Resin Out of Trees

Typically, harvesting resin involves stripping layers of outer bark and wounding the inner bark to activate the resin cells, the tree’s anti-bacterial protection.

A standard method is to cut a downward chevron of lines in the tree so that the resin would naturally flow to the center bottom, where a container could gradually collect it.

“To create the Mumia powder, the pigment manufacturer would cut or break off manageable pieces of the mummified corpses for crushing, grinding, and powdering.”

When these substances were combined in the prescribed proportions, the result was a rich, earthy, red-brown tint: a pigment advertised and sold as Mummy Brown.

A Pigment, Not a Paint

Mummy Brown wasn’t a paint, though artists sometimes used it as one when they applied it thickly. Rather, it was a brown, bituminous varnish, and when it was brushed over oil paint, you could still see much of the color beneath. And this was Mummy Brown’s power.

In Fact, An Incredibly Useful Pigment

Because it was a semi-transparent glaze, you could apply it layer on layer, letting it dry between applications. This would shadow the area in a progressively darker brown hue.

When realist artists worked in oils, this property was potent, allowing them to naturally and precisely control both the depth of warm shadows and, ironically, the life-like rendering of flesh tones.

Artists found this layered darkening effective and easy to use, and from its introduction, Mummy Brown found popularity across Europe. Merchants created and sold variations of the pigment since the 1500s. However, the first recorded sale dates back to a Paris artists’ supply shop called “À la momie,” which sold paints, varnishes, and containers of Mumia, the powdered mummy. Why would they sell just the powder? Well, it’s pretty disgusting, but we’ll get to that.

When the “Compendium of Colors” was published in London in 1797, it proclaimed that the finest brown used as a glaze by Benjamin West, President of the Royal Academy, “is the flesh of mummy, the most fleshy are the best parts.”

Uh. Yeah. OK. Calm down, color guy. Don’t make me get the hose.

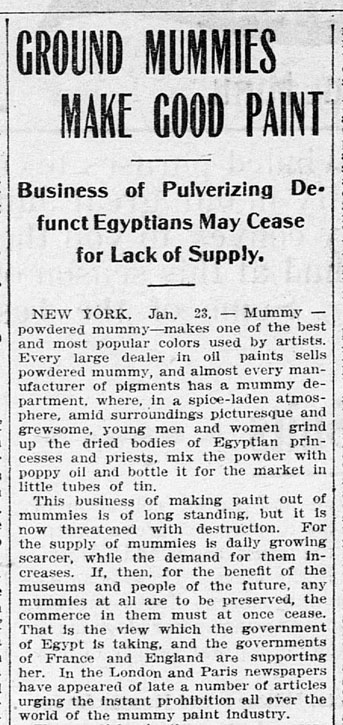

Mo’ Pigment, Mo’ Mummies

The popularity of Mummy Brown gradually increased over its more than 350-year run—almost up to the 20th century, in fact. The artist’s demand for Mummy Brown sometimes exceeded the supply of available bodies. Its uninterrupted manufacture depended on regular infusions of grindable mummies over hundreds of years.

So, where the heck did all these mummies come from?

Here There Be Mummies

Well, they mostly came from where you may have already guessed.

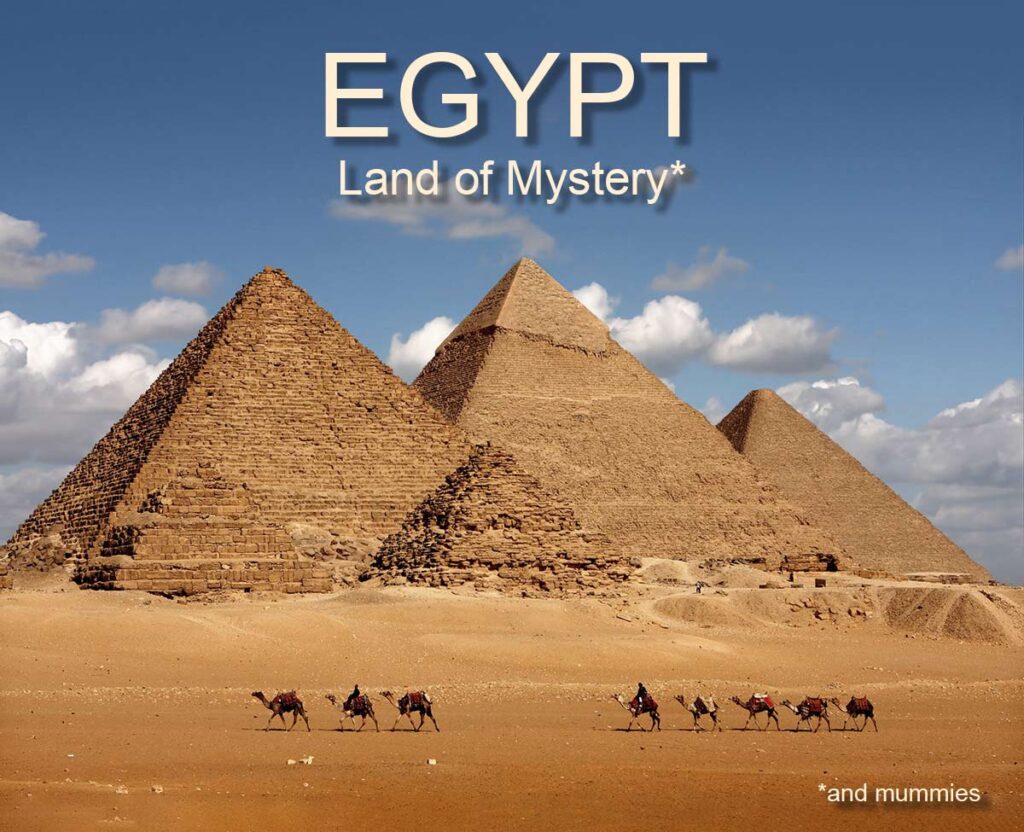

In the 1400s, traveling merchants found a novel new market. They sought to profit from trafficking mummies out of Egypt and into Europe. This burgeoning mummy trade quickly became large and very lucrative for reasons that will soon become clear.

Going as far back as the Middle Ages, mummies were considered valuable for reasons that are, in equal parts, disturbing and disgusting.

It truly was a different time.

What’s in a Mummy?

Rumor has it that when the supply of mummies was low, the corpses of slaves, criminals, or animals were sometimes substituted to manufacture the Mummy Brown pigment. But if unethical merchants resorted to this con job, the product would undoubtedly be of poor quality. That’s because it’s not just any corpse that would do. The ancient Egyptians prepared their mummies in a time-consuming, unique, and exacting process involving some exotic chemical compounds.

The Key is the Embalming Ingredients

Modern embalming fluid typically is mostly formaldehyde, but the embalming compounds used by the ancient Egyptians were slightly more exotic. Although scientists have analyzed the remnants of this substance on many mummies, the specific ingredients used still aren’t fully understood, and the formulations varied over time.

The earliest mummy that had been chemically preserved in this way was determined to be embalmed with a mixture of plant oil, aromatic plant extract, plant gum or sugar, and conifer (pine tree) resin.

When mixed into oil, pine resin provides antibacterial properties, which help stave off decay. Pine trees are not native to Egypt, and this resin would have been imported at some cost from merchant traders from the eastern Mediterranean or ones from as far away as far away as southeast Asia.

“the finest brown used as a glaze by Benjamin West, President of the Royal Academy, ‘is the flesh of mummy, the most fleshy are the best parts’…”

The embalming compound typically contained oils from cedar, juniper, and cypress trees and a plant-based gum extracted from acacia, as well as fatty acids (ricinoleic and oleic acid) derived from animal fat. Later versions of the embalming compound included beeswax, pistachio oil, and pistachio resin imported from Persia, and one more unusual, black, sticky substance that would, far in the future, become very consequential.

All About the Bitumens

Near the end of the New Kingdom of ancient Egypt (1991–1802 BCE), the embalming priests began to add bitumen (bih-TOO-min)—a thick, black, waterproof, flammable form of petroleum—to their embalming resin. This is the same tacky, black goo commonly called asphalt, tar, or sometimes pitch, used today for road construction and repair and is what roofing shingles are typically made from. You get bitumen when photosynthetic life like algae and diatoms settle in the mud at the bottom of ancient oceans or lakes and get buried for millions of years deep in the earth.

The University of Queensland pitch drop experiment was set up in 1927 to demonstrate the viscosity of bitumen (pitch). Professor Thomas Parnell of the University of Queensland poured melted bitumen into a sealed glass funnel, allowed it to cool, and then opened the bottom of the funnel. It’s some seriously thick stuff. The 8th drop fell in 2014, and the 9th one will probably happen around 2028. The experiment holds a Guinness World Record for the longest continuously running science experiment. There are two older experiments still running—The University of Oxford Electric Bell, a battery experiment where a bell has rung about 10 billion times since 1840, and The Beverly Clock at the University of Otago, New Zealand, a clock powered by variations in daily air temperature that has not had to be wound since 1864—but those experiments both suffered interruptions.

Biomarkers determined that the Egyptians got their bitumen from the nearby Dead Sea—which the Romans called Palus Asphaltites (Asphalt Lake)—likely purchasing it as a commodity from Persian traders. The Persians were the bitumen experts of the ancient world.

They Start Using Bitumen, and the Mummies Change

From this point onward, this change in the ancient Egyptians’ preservation chemistry meant that their mummies would contain a significant amount of bitumen. (Say it with me…bih-TOO-min).

Mummies would now be much darker…and browner.

Is Everything OK? You’ve Barely Touched Your Powdered Human Remains

For millennia, ancient civilizations used bitumen as a glue and for waterproofing containers, baths, and ships. But in Europe, throughout the Middle Ages, bitumen was also believed to have medicinal value as a healing compound, both topically and ingested. The supposed health benefits were originally based on the documented medicinal properties of natural bitumen obtained from the Dead Sea and elsewhere.

Specifically, in ancient Persia, it was used medicinally for a wide range of ailments, as a bone pain reliever, to speed up the healing of wounds, and to treat gastrointestinal digestive problems.

Because many ancient Egyptian mummies contained bitumen, it wasn’t much of a stretch to believe that eating mummies might cure what ails you. And—probably unsurprising knowing how people think and given mummies’ exotic origin—powdered mummy was also believed to be an aphrodisiac. For these reasons, Mumia powder was a standard product in apothecary shops, the Medieval version of drugstores.

But look, there’s a big difference between ancient Persians legitimately using pure bitumen—natural asphalt—medicinally and Medieval Europeans indiscriminately eating powdered mummies. It seems like some wires got crossed somewhere.

Apparently, that’s exactly what happened.

Before “Mumia” was the word for “mummy powder,” it was the name of the Persians’ bituminous medicine. It was the word for “bitumen” in their language. But in the 11th and 12th centuries, translators incorrectly identified Mumia, bitumen, as a substance that exuded from preserved bodies in Egyptian tombs rather than a substance mined from the Dead Sea. This confusion was further compounded by the fact that bitumen was actually used in some mummies, reinforcing the false connection. As a result, the term “Mumia” in Europe was shifted from meaning “medicinal bitumen” to meaning “mummies from Egypt”.

Outside the World of Gross Make-Believe, eating corpse powder was unlikely to have any healing properties whatsoever. But then you’re probably sick and not thinking straight, and you’re also probably living in a Medieval age of horse poop, rats, and maggoty cheese. So. Bon appetit.

A Seemingly Endless Supply of Mummies

It began as a costly procedure reserved for Egyptian royalty and the very rich. However, later in Egypt’s history, mummification became so common that it became the standard, accepted way to put the dead to rest, regardless of wealth or social status. And not just for grandpa, but for beloved pets as well.

Mummification was practiced for well over 2,000 years in ancient Egypt. Over this time, it is estimated that more than 70 million mummies were created. This meant, years later, there was no shortage of mummies to sell to willing buyers.

70 million. So many mummies.

There was such a seemingly endless number of them—in every imaginable state of physical condition—that mummy vendors would set up ad hoc shops in the streets of Cairo and Thebes to sell whatever they had on hand for significant profit to wealthy European tourists, travelers, and self-described adventurers.

Back in Europe, where the Industrial Revolution was gaining steam (literally), large numbers of human and animal mummies were ground up and shipped to England and Germany for use in fields as inexpensive fertilizer.

How’s that for a freakin’ insult? Were there no advocates anywhere for the dignity of ancient Egypt’s dead?

You must be wondering, how on earth was any of this legal?

How on Earth Was Any of This Legal?

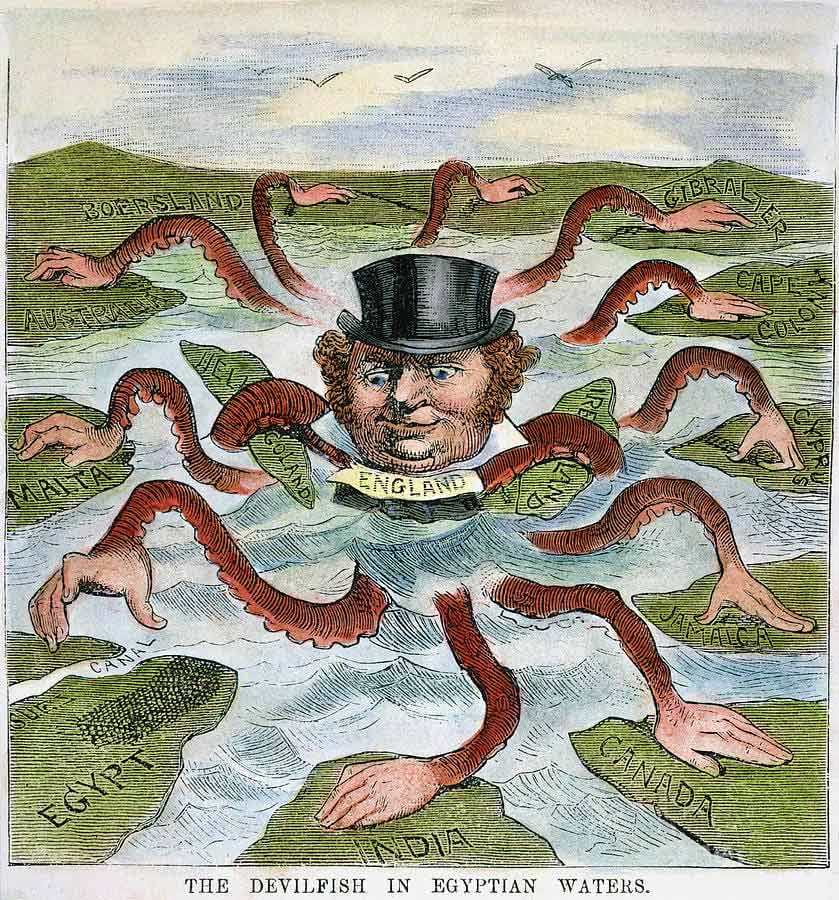

No doubt, any legitimate Egyptian government would have said it was not just illegal but an atrocity, but for 400 years, finding something that looked like a legitimate Egyptian government was difficult. Egypt had not been an independent nation since before the Middle Ages.

The Ottoman Empire Takes Over

The Mamluk Sultans ruled the area from the 1200s to the early 1500s. Then, for 300 years, the Islamic Ottoman Empire—the seat of which was in what is today Istanbul, Turkey—ruled Egypt as an “administrative division.” This began in 1517 when Ottoman Sultan Selim I (Selim the Grim) captured Cairo from the Mamluks and absorbed Egypt into the Empire.

The Ottoman Empire controlled Egypt until 1867 with only one brief, chaotic interruption when, in 1798, Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte sent 35,000 soldiers to invade and begin an occupation.

France was at war with Britain, and Napoleon intended to disrupt British trade routes. He was forced to leave in 1801, though, when he found the Egyptians to be, well, a bit of a handful. Napoleon came to realize that maintaining a major occupying force to suppress the rebellious Egyptians—who hated him and whom he mistreated—on top of his own escalating political problems back in France was more than he could juggle or, specifically, afford.

The Pasha of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, who had been the Ottoman governor since 1805, found he was able to enlist large-scale armies, big enough to challenge the Ottoman Empire. The Egyptians fought two wars of independence, and in 1841, the Pasha was recognized as the single, legitimate ruler of Egypt.

Egypt had shrugged off its shackles, and it was finally free!

“Back in Europe, where the Industrial Revolution was gaining steam (literally), large numbers of human and animal mummies were ground up and shipped to England and Germany for use in fields as inexpensive fertilizer.”

Well, for a hot minute anyway, because Egypt quickly became a “nominally autonomous tributary state” of the Ottoman Empire called The Khedivate of Egypt just a few years later, in 1867, independent on paper but under the control of the Ottoman Turkish Sultan yet again.

And, naturally, they were once again forced to pay taxes to the Sultan. The Egyptians were proud and independent people, and paying tributes to the Ottoman Sultan did not sit well with them. They had just finally gotten rid of this guy!

While Egyptians fumed about their raw deal, England’s interest in Egypt steadily rose. By 1850, the English had grown quite fond of Egyptian cotton, the best cotton in the world.

But Britain had more on their minds than cotton.

In 1869, Egypt had completed an engineering marvel: the Suez Canal, a man-made waterway that divided Africa and Asia. It allows ships to avoid the long, dangerous trip around the bottom of Africa. This opened a faster trade route between the North Atlantic and the northern Indian oceans, better connecting England by sea with major trading partners India and the Far East.

In 1882, Egyptian frustration came to a head, and the people once again rose against the Ottoman Sultan. But this time, Britain saw its own interests threatened and quickly sent troops to quell the uprising. This would mark the beginning of the Anglo-Egyptian War, which would see Britain launching a full-blown invasion and decisively and forcefully taking control of Egypt.

The battles killed over 2,000 Egyptian army, with the British suffering only 54 casualties. Britain had no legal basis for their action. Still, Egypt would become a de facto protectorate under British Colonial rule.

To add to their problems, Egypt had borrowed a fortune from European creditors to build the Suez Canal and other infrastructure and modernization projects, and they had defaulted on their loans. The British used this as a rationale to seize control of the canal even though France held most of the canal debt.

Egypt was still technically an independent nation, but the British Imperial Army had set up shop and called the shots. They were independent on paper, perhaps, but as it lived under permanent military occupation and remained a province of the Ottoman Empire, the beleaguered once-great nation was not exactly in control of its destiny.

But history doesn’t stand still, and when the Ottoman Empire was permanently dissolved in 1922, the various Ottoman territories—Egypt included—were divided between Britain, France, Greece, and Russia. Since the British had been running Egypt for forty years, it’s not hard to guess which of the four got Egypt.

So Kinda, Sorta Legal If You Squint Real Hard

In the early days of the mummy trade, Egypt was a part of the Ottoman Empire, and protecting Egypt’s precious cultural heritage was pretty much at the bottom of the Ottoman Sultan’s priorities list.

Later, the British Empire controlled the show when Egyptomania was in full swing, and mummies were the hot must-have item back home.

Exporting mummies to Europe for all kinds of unseemly purposes was clearly always unethical. However, the Muslim Ottoman sultans in charge couldn’t care less what happened to heathen mummies and artifacts for hundreds of years. And when the British took over, “legal” was anything the British government permitted.

The Demand for Mummy Brown Tapers Off

It’s thought that the popularity of the pigment fell off in the 1800s as more artists became aware of what, exactly, produced the brown in Mummy Brown. If that’s the case, then it’s hard to be sure what these artists were thinking, considering the products had “mummy” right in the name. You’d think word of this kind of thing would quickly get around.

Nonetheless, English painter Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898), a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, was said to be so upset when he discovered the pigment contained human remains that he solemnly buried his last tube of it in his garden.

It Actually Had More Problems Than Just…The You Know

Mummy Brown wasn’t perfect. It presented artists with several technical issues that undoubtedly helped contribute to its diminishing popularity.

- It exhibited poor permanence—what’s known as material instability—with a tendency to fade and change color over time and with exposure to the sun.

- It was susceptible to uneven drying and cracking when used thickly as paint.

- Color tended to vary significantly from batch to batch, depending on the color of the mummies used in making it.

- The pigment tended to be highly variable in composition and quality. It could chemically react with the paints it was applied to, affecting their color in unpredictable ways. This was because the mummies contained ammonia, fat particles, and volatile organic compounds in the resins.

Finally, as time wore on and pigment manufacturers faced mounting challenges in obtaining mummies, the availability of Mummy Brown grew increasingly spotty.

These problems encouraged artists to consider substitutes just as workable alternatives began appearing on the market.

The Era of a Gruesome Product Finally Ends

By the beginning of the 20th century, demand for and availability of Mummy Brown had dropped considerably as the supply of grindable mummies dwindled.

The Egyptian government had become quite serious about controlling the export of its culturally significant mummies and ancient artifacts, and destroying them for use as art supplies was not considered a legitimate reason to obtain them.

At the same time, suitable substitutes that had no disturbing ethical baggage had become available. Color manufacturers developed effective alternatives for Mummy Brown with all the color and properties and none of the problems. The new pigments often used kaolin (China clay) and hematite, which provided the desired rich red-brown color. These new pigments were also more stable and predictable.

The last tubes of Mummy Brown were produced by C. Roberson of London, England (est. 1810), a manufacturer of paint, ink, varnishes, and artist supplies, who continued to sell the paint, remarkably, until the 1960s. Officially, though, they had removed it from their catalog in 1933. Reportedly, C. Roberson created their last batch in 1964.

The Friday, Oct 2, 1964 issue of TIME Magazine printed a kind of obituary for Mummy Brown in a brief article titled “Techniques: The Passing of Mummy Brown.” An excerpt:

But now even Mummy Brown is gone altogether. Geoffrey Roberson-Park, managing director of London’s venerable C. Roberson color makers, regretfully admits that the firm has run out of mummies. “We might have a few odd limbs lying around somewhere,” he apologized, “but not enough to make any more paint. We sold our last complete mummy some years ago for, I think, £3. Perhaps we shouldn’t have. We certainly can’t get any more.“

Still, the Color Lives On

Today, Mummy Brown is a historical oddity, as dead as its namesake.

But there remained an artistic need for a product that could do what Mummy Brown was famous for: a red-brown that could be layered over oil paints to create progressively darker shadow and flesh tones.

Modern color manufacturers filled that demand with a corpse-brown rainbow of suitable replacements.

One such product is made by Natural Pigments, LLC of California, which says they use traditional processes and substances to make paints and pigments the way they were manufactured before 1900.

We know what you’re already thinking, and no! They do not use dead bodies! Presumably!

In their Rublev Colours line of oils, they sell a pigment called “Transparent Mummy,” which uses a combination of natural minerals—hematite, goethite, clay, and quartz— to simulate the color and effect of Mummy Brown.

“We might have a few odd limbs lying around somewhere,” he apologized, “but not enough to make any more paint. We sold our last complete mummy some years ago for, I think, £3. Perhaps we shouldn’t have. We certainly can’t get any more.”

In fact, when it comes to art supplies, modern artists have an embarrassment of riches when it comes to this color. Usually named Caput Mortuum, a nod to the color’s macabre history, manufacturers worldwide offer a range of hematite-based products in various forms, from artists’ pigment powders to paints, varnishes, pastel sticks, and colored pencils.

Disclaimer

The writers and editors of It Came From The Net strongly, STRONGLY discourage using dead bodies to manufacture products or goods of any kind.

Please don’t ever do it.

There are probably many useful things you could use instead. You could try white glue, or plastic is quite versatile. We’re positive you could make something with a 3D printer that would work instead of using body parts.

Thank you.

If you enjoyed this story, you might like our companion story about how Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt blew our understanding of Egyptian history and beliefs wide open…when his soldiers discovered The Rosetta Stone: The Amazing Key that Unlocked Ancient Egypt.